Contemporary Art – Closed Eyes, Open Questions

July 18, 2025

Contemporary art and the space of misunderstanding: Personal reflections on its relationship with a lay audience

For a long time, I believed the most important mission of contemporary visual art was to build a bridge between artwork and viewer—to connect, even when the viewer hadn’t studied art theory. I thought that if I framed my work sensitively and invited interpretations through form, even a lay audience could engage with conceptual, layered, and disquieting pieces.

But now I see differently.

This shift wasn’t theoretical—it emerged from my own life. My family’s repeated resistance to and dismissal of my work made it clear that not all misunderstandings are innocent. Sometimes, the viewer doesn’t withhold engagement out of confusion, but out of deliberate closure or even defensive reactions. Contemporary art calls for thinking, doubt, and self-reflection—experiences that can be uncomfortable or even frightening for those accustomed to familiar, safe forms.

My family’s example taught me that not everyone wants to understand. Not everyone wants to open. And that’s okay—but it’s no longer my responsibility.

I still meet countless people—clients, visitors, casual observers—whose only criterion for judging my work is whether it’s “pretty”. If yes, they accept it; if no, they reject it. In such cases, I realize: they aren’t reacting to me, but to their own limits. I don’t have to fight for recognition. It’s not my job to convince everyone of the validity of contemporary art.

However, this is not just an individual issue—it’s systemic. In many societies—especially in Hungary—people are never given the chance to learn the language of art. Visual education is minimal in schools, and art history has been removed from the secondary school curriculum. Yet to understand contemporary art requires not only sensitivity but also foundational knowledge, visual literacy, and critical thinking.

And that is precisely what authoritarian systems disallow. Critical thinking is dangerous—not only when confronting an art installation, but when questioning established power structures. A person who can read symbols, ask questions, and remain open is less likely to accept dominant narratives unquestioned.

That’s why I regard my work not only as artistic expression, but as a form of cultural resistance. My art is experimental, often grotesque, and always boundary-breaking. I’m not here to be liked by everyone. Truth-seeking comes at a price—and that’s the price I’ve willingly paid.

I now clearly distinguish between different kinds of work. If someone orders a decorative, aesthetically pleasing project, I gladly fulfill it—but I don’t confuse it with the work that truly belongs to me. Those commissions may allow me to build financial reserves, but my real energy always goes into the works that don’t cater, but challenge, disorient, and open new perspectives.

What once felt like a personal failure—the general audience’s closedness—now feels like a commentary on the cultural state of society, not on me. My mission isn’t to bring everyone along—but to steadfastly walk my own path. And if someone still wants to connect, they will come to me on their own terms. That connection is worth far more than a thousand polite but empty glances.

Examples of true connection—Contemporary artists who bridge the gap

While my personal experiences and the cultural context often place me before a wall of misunderstanding, I believe it’s crucial to realize that genuine connection between contemporary art and a lay audience is possible. In fact, there are artists who have reached wide audiences without sacrificing artistic complexity, autonomy, or social sensitivity. Here are some examples that inspire me:

🔹 JR (France)

Photographic public art, community participation

JR’s monumental black-and-white portraits appear on buildings, favelas, or border walls worldwide—frequently featuring people whose voices seldom enter public discourse. His art is not just visual but a social act: during the process, the community becomes co-creator. Thus a lay audience does not simply observe, but connects as dignified participants.

🔹 Theaster Gates (USA)

Socially engaged art, architecture, community building

In Gates’s work, bricks, music, urban decay, and human narrative all become building materials. Through projects in Chicago—libraries, cultural centers, communal spaces—his art is not an object on display but a lived experience. The lay audience isn’t passive, but a community actor whose everyday life merges with the art.

🔹 Ernesto Neto (Brazil)

Sensory sculpture, immersive installations

Neto constructs worlds from textiles, spices, scents, colors, and soft forms, inviting viewers to literally enter the work. Through touch, smell, movement, and play, an intimacy emerges where contemporary art doesn’t ask for interpretation—it demands immersion. Lay viewers understand with their bodies.

🔹 Yayoi Kusama (Japan)

Visual manifestation and psychic realms

Kusama’s infinite mirror rooms, hypnotic dot fields, and kaleidoscopic installations are at once whimsical and deeply personal. Her art visualizes anxiety, identity, and cosmic expansiveness—experiences that don’t require theoretical knowledge, only openness. And that openness is often the deepest connection.

🔹 Francis Alÿs (Belgium / Mexico)

Conceptual performance, video art

Alÿs’s works may begin with seemingly absurd gestures—a person pushing an ice cube down a street, painting soldiers’ shadows, children playing hillside games—but these simple acts reveal social and political discontinuities. Lay viewers may start by simply watching, but then they start asking. That’s where connection begins.

🔹 Banksy (UK)

Satirical street art, visual activism

Banksy’s imagery is simple yet powerful. His stencils—a masked protester throwing flowers, a girl reaching for a string of balloons—are immediately readable yet socially charged. Appearing in public spaces, gallery walls, and online platforms, his work often surprises, angers, or moves the lay viewer—eliciting responses that themselves are meaningful encounters.

🔹 Takashi Murakami (Japan)

Painting, pop-cultural iconography, cultural critique

Murakami’s loud kawaii characters and colorful motifs draw from Japanese pop culture and commercial aesthetics—but beneath that veneer lies subtle commentary on postwar identity, globalization, and consumerism. The viewer is first enchanted, then unsettled, and ultimately prompted to reflect. That layered engagement is the power of his art.

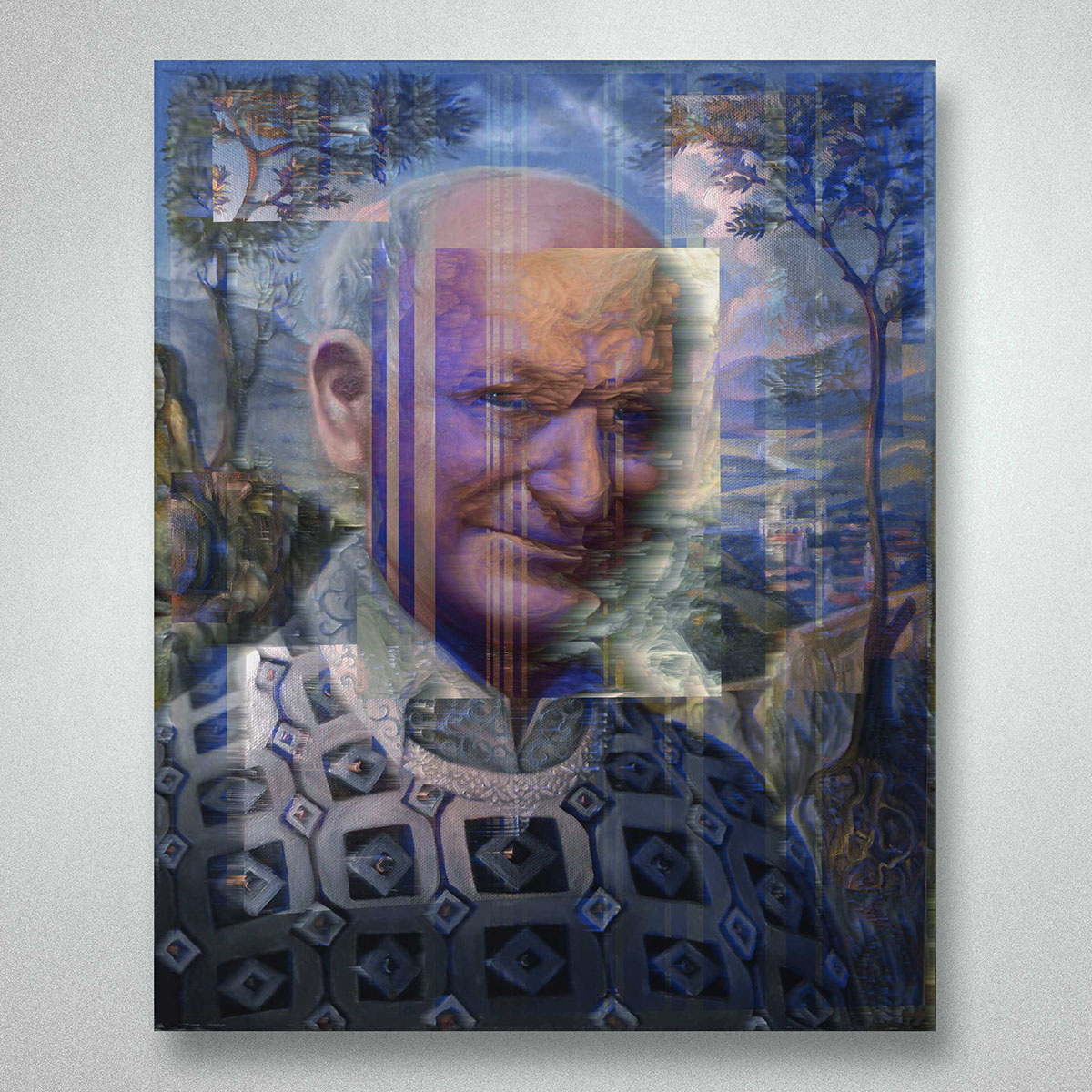

🔹 Szauder Dávid (Hungary)

Digital art, visual poetry, media art

Szauder Dávid’s works inhabit the borderlands between algorithmic logic and emotional resonance. Blending written text, visual static, moving imagery, and digital soundscapes, he creates glitch‑poetic post‑digital landscapes—complex and unfamiliar, yet emotionally intuitive. His medium becomes a bridge: through digital aesthetics, he transmits poetic, human content that resonates not just with experts but with open-minded lay audiences as well.

These examples affirm for me that connection is possible—but not in every place, and not at any cost. These artists found ways to engage not by simplifying their language to match their audience, but by awakening sensory, bodily, and cultural reflexes—thus forging relationships not through explanation, but through experience.

To me, this is deeply instructive: while I no longer try to convert everyone to contemporary art, these examples reassure me that autonomous, experimental art still has impact—when it is authentic, sensitive, and unafraid to question rather than teach.